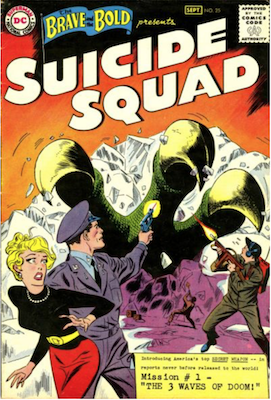

Undervalued Comics: Brave and the Bold 25, 1st Suicide Squad

Why Brave and the Bold 25 is an Undervalued Comic

As we’ve pointed out in other articles within this Undervalued Comic Books series, DC comics just don’t seem to get the same pricing buzz-bump as their Marvel brethren.

It’s also worth noting that both Suicide Squad movies were woven from the narrative cloth of the team’s more recent iterations. That version only dates to 1986, well after the time when new comics were hoarded en masse by eager fanboys, to be hermetically sealed in plastic sleeves immediately upon release.

Plentiful to the point of being commonplace, the first appearance of the modern Squad, from Legends #3, goes for $45 in CGC 9.8. Meanwhile, the introduction of series lynchpin Amanda Waller, in Legends #1, fetches no better than $100 in the same near-perfect grade.

But thankfully for the serious collector, Suicide Squad roots run much deeper than that. In fact, the Suicide Squad was one of the earliest additions to the DC Universe as we know it today. Unfortunately, early in is sometimes early out.

The original Suicide Squad lasted all of six issues. And then it was gone, largely forgotten, overlooked for decades as anything other than a curiosity; a rare misfire of the early Silver Age at DC.

Brave and Bold #25: 1st panel featuring Rick Flag

Brave and Bold #25: 1st panel featuring Rick FlagBut today, that initial lack of fan allure lends those six books the scarcity they need, which — when coupled with historic significance and modern curiosity — translates into investment potential. And all six books, particularly the first, are, we think, ripe for speculation, if only because casual fans don’t seem to have yet discovered them, making these lost gems a bargain worth getting while the getting is good.

After all, we can’t imagine these earliest Suicide Squad books will be ignored for much longer. With DC Studios co-head James Gunn having won his new role largely on the strength of his Suicide Squad movie, we have to believe we’ve not seen the last of DC’s IP cannon fodder.

And sure, Suicide Squad field leader Col. Rick Flag did meet his end in Gunn’s flick. But, according to DC’s comic book continuity, that was Rick Flag III. His father, Rick Flag Jr., fought monsters that’d make Starro blush from inadequacy, while Rick Flag Sr. could bitch-slap a tyrannosaur for breakfast and still kick the snot out of a stegosaur by lunch.

Thus, it can’t be hard to imagine a flashback scene, at least, in some future Suicide Squad film, harkening back to these two earlier alpha-male Pickle Ricks. Especially considering they were both the same guy.

What’s that you ask, eyebrows akimbo? Rick Flag Sr. and Rick Flag Jr. are the same guy?? Don’t worry, it’s comics. It’s complicated. We’ll explain.

A Brave Beginning

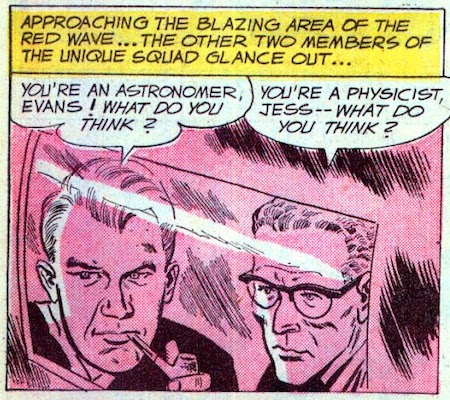

The Suicide Squad made its debut in The Brave and the Bold 25, which hit newsstands nationwide on June 25, 1959. Apart from being the first appearance of both Rick Flag and the Suicide Squad — the other primordial members being pretty medic Karin Grace, brainy astronomer Dr. Hugh Evans, and young physicist Jess Bright — this issue also marked a paradigm shift for the title.

In its first 24 outings, B&B featured two-fisted heroes from times past, such as Robin Hood, the Silent Knight, and Viking Price. But following the stellar success of DC’s try-out book, Showcase, B&B was recast as a sort of sister series, to help audition new characters and concepts for potential inclusion into the burgeoning DC pantheon. First up was the Suicide Squad, created by Robert Kanigher, editor of DC’s war books and driving creative force of the earlier action-man version of B&B.

However, instead of his previous B&B collaborators, Kanigher chose as his Suicide Squad artist, Ross Andru, with whom he also produced Wonder Woman.

Yes, Kanigher ran DC’s line of war titles and Wonder Woman.

Because reasons.

Actually, joking aside, there were reasons. One of them being that Kanigher was amazingly prolific. This was due in part to his creative process, in which he utterly eschewed the peremptory step of drafting anything resembling a plot.

The legend is that Kanigher prided himself on being able to pop a sheet of blank paper into a typewriter and start writing Page 1 without the foggiest notion what was going to happen on Page 2. He’d just figure it out as he went along, somehow satisfactorily wrapping it all up in the exact number of assigned pages.

Most of the time, this method worked out pretty well. By his own account, Kanigher created the Metal Men and crafted their complete first issue over a single weekend, done as a pinch-hit when another book scheduled for the Showcase treatment was deemed at the last minute to be unusable.

By general acclaim, the first dozen issues or so of Metal Men were fabulous, with incredibly strong sales to verify the quality of the work. But then Kanigher seemed to lose interest in that one and it soon sputtered out into issue-after-issue of syncopatic sameness.

Kanigher’s Suicide Squad had many of those same qualities, just on a shorter timespan. Seemingly written in Kanigher’s usual stream-of-consciousness fashion, Brave and the Bold #25 has a strong start, with a powerful hook, but the potential quickly peters out.

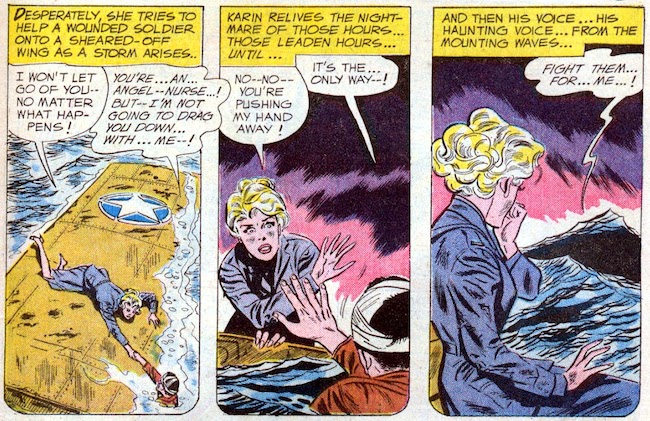

Brave and the Bold 25: Karin's Titanic Moment

Brave and the Bold 25: Karin's Titanic MomentNot the Only Squad in Town

It should also be noted that, while Kanigher was too creative to straight-up plagiarize, his Suicide Squad nonetheless shares much in common with many other books DC was publishing at the time, particularly Challengers of the Unknown.

Said to have been created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby for their defunct Mainline Comics publishing house, the Challengers debuted in DC’s Showcase #6 (on-sale November 6, 1956). They were four guys who, surviving a plane crash and believing themselves to be “living on borrowed time” anyway, team up to risk all in pursuit of the unknown.

The Suicide Squad tipped that, if not on its head, at least on its side, by making its foursome sole survivors of separate incidents, now bound by remorse to carry on in place of those who, but for happenstance, might have been them.

Yes, survivor’s guilt was heady stuff for a 1959 comic book aimed at ten-year-olds. And that’s just on thematic grounds, never mind the title itself.

Consider, Brave and the Bold 25 came out barely five years after establishment of the Comics Code Authority, whose strict rules forbade use of even so benign a word as “weird” in a comic book title. How ever did “suicide” make it past the censors?

One wonders if it was perhaps to assuage the CCA after the fact that Kanigher had letterer Ira Schnapps add “Task Force X” to the Suicide Squad logo starting with the team’s second appearance, perhaps to reinforce the notion that this was, in fact, the real name of the team, with “Suicide Squad” just a sardonic sobriquet thrown around by the regular military personnel that assigned and supported its missions.

As to the Squad’s first recorded outing, Kanigher takes so much time establishing the menace, and then the back stories of both Flag and Grace — not to mention their romantic entanglement — that Evans and Bright get short-shrift.

Joined at the hip like Frik & Frak in both personality and narrative contribution, they seem to exist solely for the purpose of declaring scientific discoveries that suggest Rick’s next bold action. Consigned to a joint backstory measured in panels, rather than the pages allowed for the others, Evans and Bright are, in this first story anyway, cardboard cutouts, who, like non-player characters in a video game, function merely to move the story along.

On top of that, one does get the feeling Kanigher found himself running out of page space fast, as the first Squad outing wraps up pretty quickly, with the team transferring from their “flying laboratory” to a waiting rocket ship for an unlikely trip first to the moon, then around the sun, where solar gravity sucks the monster-du-jour right off their hull. Because that’s totally how gravity works.

Don’t get us wrong, we’re not trying to discourage you from buying Brave and the Bold #25 by saying it’s weird and goofy. Comic books, especially early comic books, are weird and goofy. You wouldn’t buy any at all if that’s what was holding you back.

The first Suicide Squad story is fun, which is what a good comic book should be. It’s just not as strong overall as Kanigher’s usual stuff, a fact that appears to have been reflected in low sales.

Another reason for apparent low sales on the OG Suicide Squad might be that, in terms of style, it was a tale out of time. At the dawn of the Silver Age, things like the Barry Allen reboot of The Flash (which Kanigher also created) had a fresh, forward-looking sheen. It was bright. It was confident. It was of an era to come. It was The Right Stuff.

But Kanigher’s Suicide Squad wasn’t quite there yet. It instead harkened back to the zeitgeist of comicdom’s Atom Age — a world of nuclear annihilation and bug-eyed-monsters done up like drive-in B-movies filmed in four colors, where characters do not control their world so much as try to escape it. Or maybe that “Suicide” title was just a tad off-putting to pubescent Baby Boomers. Who knows?

At any rate, after a three-issue run is B&B #25-27 (published from June 25 to October 27, 1959), the original Suicide Squad got a second shot to prove itself in issues #37-39 (released between June 22 and October 26, 1961).

And that was that, making the Suicide Squad the first tryout in either B&B or Showcase to not graduate into its own title, or to at least land a starring role in one of DC’s anthology books.

It probably didn’t help that the Challengers by then did have their own series, making the Suicide Squad’s schtick of, “damn the danger, we should be dead anyway,” seem fairly redundant.

Moreover, while the Challengers established the template for adventure-bound quartets — the math being Boss Guy + Brainy Guy + Brawny Guy + Barely Adult Guy — that model was copied in rapid-fire fashion by, in turn, Rip Hunter’s Time Masters, the Suicide Squad, the Sea Devils, Cave Carson & Crew, and finally, to greatest effect, once the wheel had turned back to Kirby, the Fantastic Four.

All similar teams. All launched in a narrow three-year window between 1959 and 1961 — the only change being that, in every foursome subsequent to the Challengers, Boss Guy was combined with either Brainy Guy or Brawny Guy, opening a spot for Guy #4 to instead be, not a guy, but a pretty girl.

So, failing to catch fire at ignition, the original Suicide Squad pretty quickly lost any market niche it might have commandeered.

Brave and the Bold 25: Monster manipulation

Brave and the Bold 25: Monster manipulationA Legion of Super-Ricks

Now, at this point you’re probably asking, “So, what was the deal with multiple Rick Flags?”

Well, shortly after the first trio of Suicide Squad adventures, Kanigher and Andru launched a new series in Star Spangled War Stories #90 titled “The War that Time Forgot.” Think army men vs. dinosaurs and you won’t have to think much harder than that.

The series ran semi-regularly, with the soldiers generally being the anonymous equivalent of Star Trek red shirts, only in helmets and camo gear. The series had very few continuing characters on the army end, but starting with SSWS #110 (on-sale June 20, 1963), Kanigher began referring to them as the Suicide Squadron. By #116 this was truncated back to Suicide Squad.

In all, the Suicide Squad designation was used in 11 issues of SSWS, ending with #137. Neither Rick Flag, nor any of the original members of Task Force X appeared to help battle the prehistoric denizens of Dinosaur Island. These stories came out almost two years after Rick & Company’s last appearance.

Kanigher was just repurposing a good name.

Brave and the Bold #25: Suicide Squad Also-Rans

Brave and the Bold #25: Suicide Squad Also-RansBut when the Suicide Squad got its 1986 reboot, writer John Ostrander folded in all previous versions of the team into a single narrative through line. In Secret Origins #14 (on-sale February 12, 1987), it was revealed that a Rick Flag Sr. was present during the World War II stories, leading that Suicide Squad of misfit soldiers as they tried to re-conquer Dinosaur Island.

This revelation made the original Rick Flag of Task Force X a Rick Flag Junior, thus re-casting the then-modern day Flag third-of-his-name.

And, yes, we admit all that explanation was a bit of the long way around the barn just to get back to the bottom line, to wit: The Brave and the Bold #25 is an important comic book. It is worthy of both your attention and your dollars.

Because — and while this may go without saying, let’s say it anyway — the entire Suicide Squad franchise, including recent and future films, could not have happened without it.

Guide to Brave and the Bold 25 Comic Book Values

- CGC 9.2 — $25,000 (Jul. 2015)

- CGC 8.5 — $16,700 [Savannah Pedigree] (Jul. 2016)

- CGC 8.5 — $6,950 (Apr. 2021)

- CGC 8.0 — $2,390 (Sep. 2014)

- CGC 7.0 — $3,199 (Oct. 2020)

- CGC 6.5 — $2,310 (Apr. 2021)

- CGC 6.0 — $1,678

- CGC 5.5 — $1,999

- CGC 5.0 — $1,688

- CGC 4.5 — $1,240

- CGC 4.0 — $800

- CGC 3.5 — $800

- CGC 3.0 — $485

- CGC 2.5 — $430

- CGC 2.0 — $314

- CGC 1.8 — $299 (Dec. 2018)

- CGC 1.5 — $300

- CGC 1.0 — $310 (Jan. 2021)

- CGC 0.5 — $200 (Jun. 2019)

As previously stated, it seems more likely than not that in any future movie or streaming show starring the Squad, one for both original-flavor Flags are bound to get some form of treatment.

And then you will surely wish you owned Brave and the Bold 25. So, why not grab it now, while it’s still super affordable, at least comparatively, considering what it is?

It won’t be an easy grab, we grant you. Remember, it didn’t sell well when new, and those issues that were purchased were not treasured as much by the fanboys with their spandex fever. To date, CGC has graded just 302 copies, including 290 with the coveted “Universal” label. And of those certified books, just 11 are graded 7.5 or better.

But you might be able to land one in a lower grade, with at least 20 examples certified at each level from 2.0 to 5.0. While a 5.0 recently sold for more than $1,600, nothing below a 4.5 has yet broken into four figures. So, it’s super affordable. But that won’t last long.

When you look at the chart above, you can see several examples of Brave and the Bold 25 selling in a given grade for more than copies one-half or even one full grade point better — a telltale sign of a book trying to break out and find a higher level, even absent additional appearances in other media.

All of that — recent sales trends, historical relevance, market scarcity, and mainstream popularity, not to mention the likelihood of future film adaptations bound to build even greater public awareness — adds up to make the first appearance of the original Suicide Squad in The Brave and the Bold #25 an “undervalued comic” you should invest in.

Have this book? Click to appraise its value or Consign Yours for Auction!

Suicide Squad movie poster

Suicide Squad movie posterINDEX OF UNDERVALUED COMIC BOOKS

Related Pages on Sell My Comic Books

Brave and the Bold Comic Book Price Guide

DC Comic Superheroes in Brave and the Bold 25