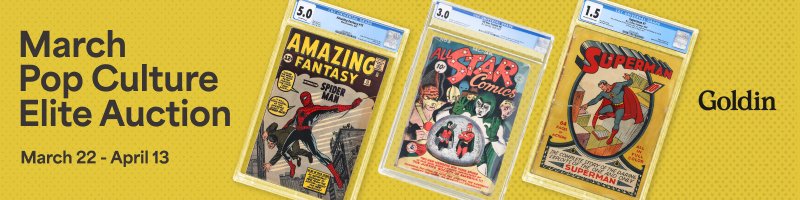

Undervalued Comics: Detective Comics 233, 1st Bat-Woman

Why Detective Comics 233 is an Undervalued Comic

When we turned you on to the investment potential of Batman #139, because it featured the first appearance of the first Batgirl, you didn't think we'd neglect her mentor, Batwoman, did you?

Well, here it is, the debut of the original Batwoman in Detective Comics #233.

And it's undervalued for all the same reasons:

- It's not trading for what one would think it should, considering its historical significance;

- That significance is not just a simple first appearance, but related to back-room action that changed the publishing paradigm;

- It's not exactly common in any grade, but is particularly rare in high grade; and

- It's had recent outlying sales highs at the top and bottom of the grading chart, indicating room for movement in the middle.

To quickly review what makes this book special, other than it containing the first appearance of Batwoman, we have to talk about why DC felt the need to create her in the first place.

By the close of the Golden Age, comic books were starting to draw the hairy eyeball from authority figures hard-pressed to explain the lack of regard young baby boomers seemed to have for authority figures.

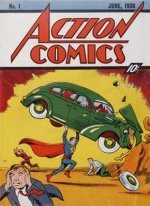

Horror in the Nursery!

Horror in the Nursery!In search of a scapegoat, this crowd made a more-than-willing audience when psychiatrist Dr. Fredric Wertham began to claim that comic books didn't just reflect juvenile delinquency — they actually caused it! It seems most of the juvenile delinquents in the good doctor's study group read comics, so, ya know, in his mind at least, it tracked.

But the anti-comics crusade really got rolling with the March 27, 1948, issue of Collier's Weekly, in an article by New York Herald Tribune reporter Judith Crist, under the not-at-all sensationalistic title, "Horror in the Nursery."

That took Wertham’s poison pen out of academia and duped it straight into American homes. His follow-up symposium was reported on in the May issue of the Saturday Review of Literature, under the title, "The Comics . . . Very Funny."

That one probably didn't gain much traction — more academia — but then the article got abridged in the August Reader’s Digest, a nightstand necessity that was effectively the Twitter of its day. And if Collier's sparked consternation within the tea-and-crumpets crowd, Reader’s Digest boiled over outrage among the hoi polloi. Suddenly, everyone, everywhere had a target to explain "kids today."

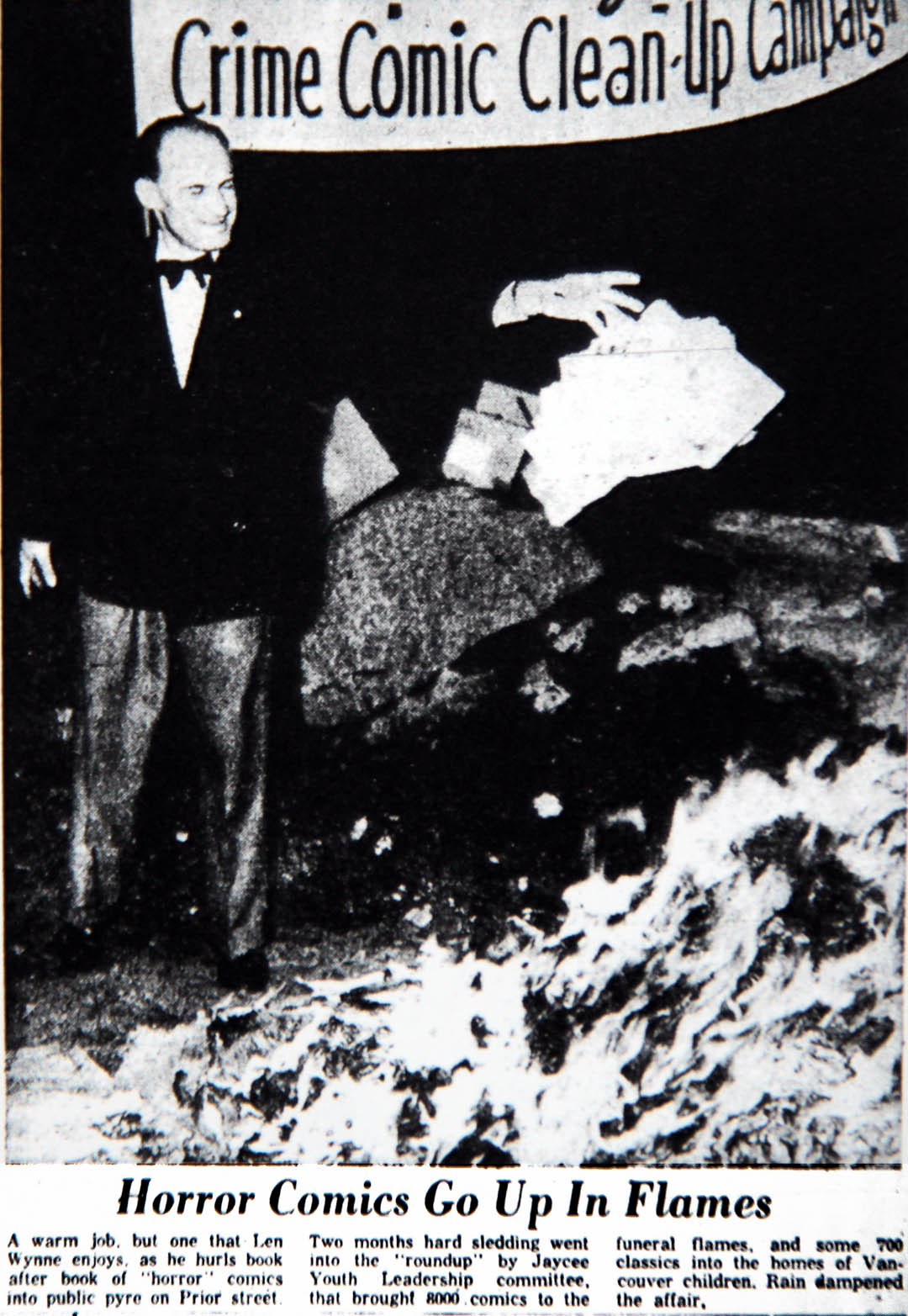

SOTI: Horror Comic Books Burning

SOTI: Horror Comic Books BurningIn October 26, 1948, Spencer, West Virginia, held the nation's first comic book bonfire. In December, residents in Binghamton, New York, went one better, going door-to-door, firing off a four-color fusillade that torched more than 2,000 of the presumably puerile periodicals.

By 1949, even the guy who invented the modern comic book format, former Eastern Color Press Sale Manager Harry Wildenberg, was trying to distance himself, telling Catholic weekly The Commoneal, he would never have done it if he'd know what comics would come to.

"I'm glad parents and educators are waking up to the menace of the comic books," he said.

By then, several cities had passed ordinances that ran the range from restricting to outright banning the sale of comic books.

DC Comics escaped most of the early wrath. After all, it published wholesome comics, not at all like the crime and horror books that sunk its competitors into the soup.

It even managed to sidestep an early self-censoring organization, the Association of Comic Magazined Publishers (ACMP), having long-since set up its own in-house advisory board made up of prominent educators, psychologists, and child-wellness professionals.

Detective Comics #233: Batwoman to Unmask Batman?

Detective Comics #233: Batwoman to Unmask Batman?But then the bomb dropped.

In 1954, Wertham published his magnum opus, Seduction of the Innocent, self-aggrandizing it all the way to a US Senate sub-committee hearing into the crisis of uncontrollable kids.

In his book and in his Senate testimony, Wertham criticized Superman as an anti-American power fantasy which insinuated itself between parents and children.

"Formerly, the child wanted to be like daddy or mommy," he said. "Now they skip you, they bypass you. They want to be like Superman, not like the hard working, prosaic father and mother."

But worse, at least for the times, was Wertham's takedown of the caped crusader. Batman, he claimed, promoted homosexual play, leading to deviant, perverse behavior.

Citing panels from the comics that showed Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson waking up together in the same room — sometimes even in the same bed, Wertham said Batman represented a homo-erotic fantasy of living in close confines with a young boy.

And by training this boy, dressing him in a garish, brightly-colored, bare-legged costume, and then leading him on dangerous adventures designed to create an intimate man/boy bond, Batman was what we'd call in modern parlance, a "groomer."

Throw in Alfred the Butler, and Wayne Manor was a veritable gay sex orgy of sin and degradation.

What could DC do in light of these accusations? Well, it seemingly did not hesitate to join the ACMP's successor organization, the Comics Code Authority.

And, after first beefing up appearances of Batman gal pal Vicki Vale, DC introduced a new love interest for its clearly hetero Bat-Dude.

Detective Comics #233: Batwoman Origin

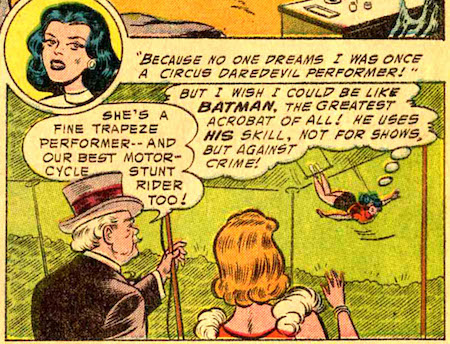

Detective Comics #233: Batwoman OriginPublished on May 24, 1956, Detective Comics 233 gave us Kathy Kane, the Batwoman, in a story written by Edmond Hamilton and drawn by Sheldon Moldoff.

Kathy shared a surname with Batman's bylined creator Bob Kane, and maybe that was intentional, designed to lend her clout. In origin, she was a strange mix of Dick Grayson and Bruce Wayne.

Like Dick, she was a circus performer, equally adept on the trapeze, or a tricked-out motorcycle. Like Bruce, she inherited a fortune and chose to use it fighting crime, dressing like a bat because criminals are a cowardly and superstitious lot.

Actually, that's not true. She did it because she had the hots for Batman. And Batman liked her, too. He liked her because — get this kids — Batwoman is a girl!

And just to drive home what some today might call her cisgender stereotype, Batwoman didn't employ a utility belt. She carried a purse. Honest to God, an actual purse!

And her Bat-gimmicks were not Bat-themed. They were She-themed, such as a light-reflecting compact mirror, a cloud-creating powder puff, and a charm bracelet that doubled as a pair of handcuffs.

Later on, as we've previously noted, Bat-Girl came along to press home the point that Robin also liked girls. At least then. We now have a different Robin for a different day

So, Kathy came with a backstory of half-buried sexual repression. She was invented to be Batman's beard.

Guide to Detective Comics 233 Comic Book Values

If you want to invest in her first appearance, there are not a lot of high-grade options to be had. Not unless you chance across a raw copy not yet sent in for certification.

The CGC census reports just 247 Universal label copies of Detective Comics 233. Add in qualified grades, signed books, and restored copies, and we only get to 266.

Detective Comics #233: Holy Bat-Love, Batman!

Detective Comics #233: Holy Bat-Love, Batman!Of those 266 slabbed books, just 12 exist in 7.5 or better, with none above 9.0 — just barely scratching the surface of near mint.

In January 2001, one of the two existing 9.0 copies sold for $26,400. Meanwhile, at the other end of the scale, a 1.0 recently sold for $1,185, while a 1.8 drew $1,200.

We've said before in other articles within this Undervalued Comic Books series that, in our experience, it's the high-grade investment copies and the low-grade vanity books that tend to mover the needle first. They then drag the mid-grades to a new mean.

And even though the CW cancelled its Batwoman TV show, and Discovery head David Zaslav scrapped a nearly-finished Batgirl movie, the lady bats aren't going anywhere.

With more than half of the comics DC publishes each month now starring Batman or some member of the Bat-Family, you just know a new Batwoman will come along, in comics and in other media soon. When she does, comic book fans will clamor more than ever for the character's first appearance.

So, yeah, we don't think those mid-grades have quite found their level yet.

But check out the chart of recent sales below, and tell us what you think.

- CGC 9.0 — $26,400

- CGC 8.0 — $1,912 (July 2012)

- CGC 7.5 — $7,768 (Aug. 2017)

- CGC 7.0 — $5,520

- CGC 6.5 — $4,600 (Mar. 2019)

- CGC 6.0 — $3,942

- CGC 5.5 — $3,695

- CGC 5.0 — $2,900

- CGC 4.5 — $2,316

- CGC 4.0 — $2,160

- CGC 3.5 — $1,998

- CGC 3.0 — $1,964

- CGC 2.5 — $1,133

- CGC 2.0 — $658 (Dec. 2019)

- CGC 1.8 — $1,200

- CGC 1.5 — $900

- CGC 1.0 — $1,185

- CGC 0.5 — $400 (July 2020)

Have this book? Click to appraise its value or Consign Yours for Auction!

INDEX OF UNDERVALUED COMIC BOOKS

Related Pages on Sell My Comic Books

Most Expensive Silver Age Comic Books

Sell My Comic Books is the Number One Buyer of Detective Comics!