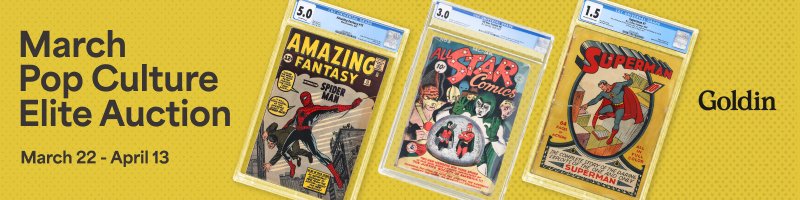

Undervalued Comics: FOOM 2, Friends of Old Marvel 2, 1st pre-Appearance of Wolverine

Why FOOM 2 is an Undervalued Comic

For comic book collectors, the hottest collectible isn't always a comic book. Especially when said non-comic contains the first appearance of a beloved comic book character.

Take, for example, FOOM #2, published on or about July 1, 1973. It contains the first appearance in any Marvel publication of Wolverine — more than a year before Incredible Hulk #181.

Oh, that catch your attention, did it? We bet.

But who is this proto-Wolverine, you ask? Or, maybe more importantly — what the heck is a FOOM?

FOOM is an acronym. A pure Stan Lee-ism, it stands for Friends Of Ol' Marvel. In printed form, FOOM was Marvel's in-house fan mag, produced quarterly for 22 issues, from 1973 to 1978.

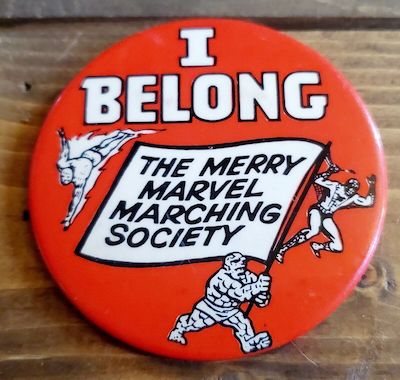

Merry Marvel Marching Society pin

Merry Marvel Marching Society pinFOOM was in many ways a successor to the Merry Marvel Marching Society, which in the Silver Age helped network comic book fans from across the county.

As more and more fans connected, they formed local clubs and, armed with carbon paper and mimeograph machines, they circulated amateur newsletters to celebrate their shared love for Stan the Man and his House of Ideas.

But by the 1970s these amateur press offerings had evolved into virtual trade magazines of an increasingly sophisticated calibre, some with national distribution.

Having taken note of this trend, comic book legend Jim Steranko happened to be in the Marvel Bullpen one day when he chatted up Stan on the topic. Maybe it was time to update the MMMS for a new generation, they reasoned.

After all, Marvel could hardly allow fans to produce news of its doings in a livelier, more up-to-date, and better produced fashion than what Marvel itself could do.

So, if you think of the early fanzines as a sort of analog Twitter, FOOM was effectively Marvel's Bronze Age Facebook page.

DC had the same idea around the same time, putting out a pro-zine of its own, with more polish but less flair, titled The Amazing World of DC Comics.

In the first FOOM, Steranko announced a contest, inviting fans to send in ideas for new characters of their own design, done in the mighty Marvel manner. The best entry, it was promised, would see publication in an actual Marvel comic book.

That never happened. Or at least not right away. Entries were published in FOOM #2-4, with honorable mentions and a grand prize winner named in #3. But the best in class — a super-villain named Humus Sapiens, created by Pittsburgh resident Michael A. Barreiro — didn't see the light of day until Thunderbolts #54, in 2001, a mere 28 years later.

Of course, aspiring artists of the day didn't care. They saw the contest as a foot in the door. And FOOM does contain the first published work of many future comics pros. Among others, #2 features Bongo Comics' Bill Morrison, Nexus co-creator Save Rude, and Black Lightning's first artist, Trevor Von Eeden.

Those issues have value for that reason alone. That's probably why nearly a quarter of all FOOM #2 copies graded by CGC to date — 43 of 184 — sport the yellow Signature Series label.

But if you do score a signed copy, the autograph you want is Andy Olsen.

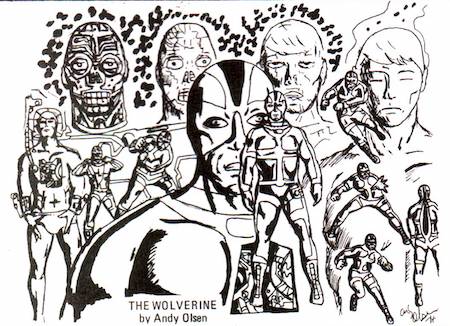

FOOM 2 The Wolverine by Andy Olsen

FOOM 2 The Wolverine by Andy OlsenWho's that, you ask? Just the real creator of Wolverine, is all.

At least that's what some say. Including Andy.

What the Florida native submitted to the FOOM contest was a character called "The Wolverine." And his version can be said to bear a passing similarity to the Freddie-fingered berserker we all know and love.

Both have a tiger stripe costume-motif of sorts, meant to mimic markings on the actual animal. Both also have metal skeletons. And a transformation sequence Olsen drew into his submission can been interpreted as his Wolverine undergoing the skeletal replacement Marvel's version is famous for, or an example of his "healing factor" in action.

But, in truth, Olsen's character looks more like a cyborg of some sort, closer to Deathlok than Wolverine.

Even so, Olsen, who did grow up to be a graphic artist, has expressed some bitterness over the supposed swipe. Speaking to Rich Johnston of website Bleeding Cool in 2014, Olsen said he outgrew comics shortly after submitting his contest entry, and had no idea his proposed hero name had been appropriated until the chance spotting of an X-Men comic when he was in college.

The biggest insult, Olsen said — and here one has to recall the state of the X-Men franchise before the all-new, all-different take from writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum — wasn't that Marvel used his character. It was that they stuck him in the X-Men!

"Of all the Marvel heroes, [the] X-Men I felt were the bottom feeders," he told Johnston.

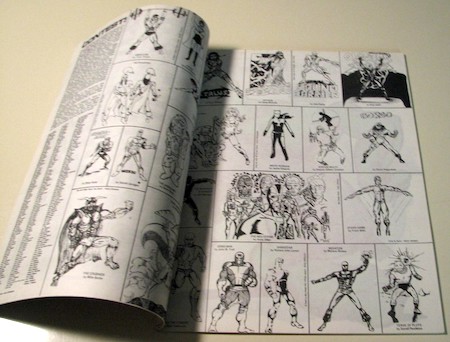

FOOM 2 The Wolverine Full Page

FOOM 2 The Wolverine Full PageIn that interview, Olsen did not seem to remember much of what his 16-year-old self intended when creating his version of "The Wolverine," needing to use his published drawing for reference. Even so, he says, he considered pressing suit.

"I felt rather used and stupid," he said. "My regard for Marvel and Stan Lee was so high it never dawned on me the contest was harvesting concepts to breathe some freshness into their line up."

Did Marvel really steal Olsen's idea? Well, the names match. That much is certain. And we do know Wein created Wolverine at the behest of Marvel's then editor-in-chief Roy Thomas.

In a 2019 release to CBR.com, Thomas said Wolverine was his concept. The directive to Wein, he said, was to make the character Canadian, short, and quick-tempered, in that order of importance.

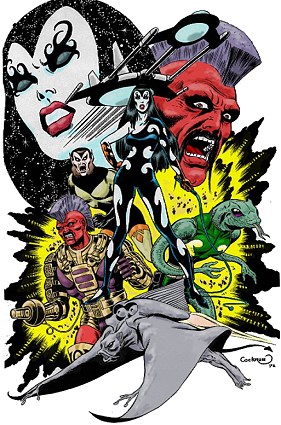

Had Thomas seen Olsen's character? Possibly. We might even allow probably. But did he remember it, that's the question. Thomas made no note of Olsen in his CBR piece, but he did reference Cockrum, who always claimed to have shown Thomas his designs for a character he also called Wolverine.

Created when Cockum was at DC working on the Legion of Super-Heroes, this werewolf-inspired Wolverine was later recycled to be Fang, of the Imperial Guard. As an in-joke, Cockrum put Wolverine in Fang's costume in X-Men #107, and reportedly would haver kept him in it, had John Byrne not replaced him with the very next issue and, hating the Fang suit, immediately changed it back.

But Thomas claims no memory of Cockrum's Wolverine. The proof, he says, is that "Wolverine" almost didn't make the cut as a codename.

"If I had taken the name from Dave, then I wouldn't have been debating in my mind for a short time, before the meeting with Len Wein, about whether to call the hero Wolverine or Badger," he said.

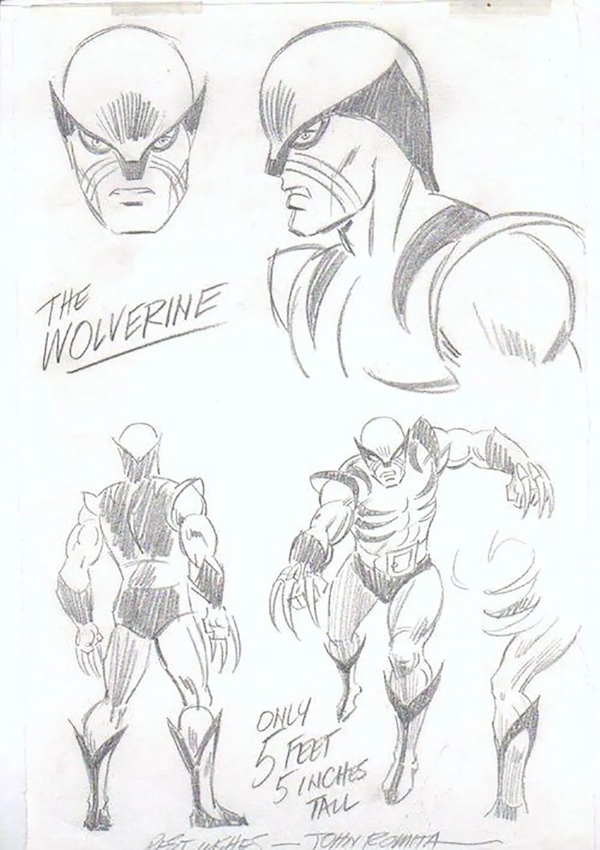

That explanation might also be applied to Olsen's creation. Or, possibly, the cynic might say, meant to distract from it. At any rate, the design for the Wolverine we know came from John Romita, who added the claws of his own initiative.

In his interview, Olsen said it never occurred to him to give claws to his version.

"The details . . . elude me," he said, "but looking back at the sketch, he seemed to have a metal skeleton and no claws, because I couldn't imagine a super-hero scratching an opponent. Sissies scratch."

And on the hunt for distinctions, it should be noted that Wolverine was a bit of a slow burn. He did not spring from whole cloth as the character we know today.

Cockrum Wolverine

Cockrum Wolverine Romita Wolverine

Romita WolverineWein has said he envisioned Romita's claws being glove accessories, not actual body parts. And after Wolverine got tossed into the X-Men mix, the first instinct of writer Chris Claremont's was to make him an actual wolverine mutated into human form by the High Evolutionary.

An oblique reference to this "unique nature" was even made in X-Men #98.

The first reference to Wolverine's healing factor and "unbreakable bones" was not made until X-Men #116. The source of the skeletal invulnerability — "about three million bucks worth of adamantium" — was not overtly stated until X-Men #126, six full years after Olsen's contest submission.

So, did Olsen truly get ripped off? Even he says it's a matter of perspective.

"Is this a case of ripping off a naïve kid's concept or simply a large multi-million dollar publishing company creating a character completely on its own and this [is] all an interesting coincidence," he asked Johnston, rhetorically.

But however Wolverine developed, rather from Olsen's idea or independently, FOOM #2 does mark the first use of the Wolverine name applied to a super-human within a Marvel comic. And that's recently marked the book as a must-have curiously for hard-core collectors.

Guide to FOOM 2 Comic Book Values

As little as five years ago, a copy of FOOM 2 in CGC 9.2 might fetch no more than $200. Even as late as 2020, $250 was the going rate for an 8.0.

But within the last year an 8.5 has sold for $650, a 9.4 for $1,499, and a near perfect 9.8 for an astounding $2,750.It seems that as Incredible Hulk #181 hit the stratosphere, and even Incredible Hulk #180 — the so-called "poor man's 181" — vaulted out of reach, budget-conscious fans have turned to the few other pre-X-Men Wolverine books out there.

That's a pool limited to a one-page cameo in Incredible Hulk #182, and house ads from Daredevil #115, Marvel Premiere #19, and Thor #229, all published between Hulk #180 and #181.

And, of course, there's Olsen's Wolverine-in-name-only.

So, find a copy of FOOM #2 and you could flip it for some fast cast, at least if you can manage to do so before rapidly rising prices hit a plateau point.

Or, considering CGC records show just three certified copies in 5.0 or below, find a low-grade copy and you could fill a market niche, as more and more of the high-grade versions top $1,000.

- CGC 9.8 — $2,750

- CGC 9.6 — $1,247

- CGC 9.4 — $1,499

- CGC 9.2 — $206 (Feb. 2017)

- CGC 9.0 — $178 (Mar. 2020)

- CGC 8.5 — $650

- CGC 8.0 — $250 (Feb. 2020)

- CGC 7.5 — $573

- CGC 7.0 — $288

- CGC 6.5 — $398

- CGC 5.0 — $170

Have this book? Click to appraise its value or Consign Yours for Auction!

INDEX OF UNDERVALUED COMIC BOOKS

Related Pages on Sell My Comic Books

Marvel Comics Characters in FOOM 2